How does Toxoplasma initiate infection in a new host?

When initiating infection in a new host, Toxoplasma must cross the intestinal mucosa. The molecular mechanisms underlying this process are unknown.

Toxoplasma secretes many proteins into the host cells to modulate host processes, such as host immune responses and cell cycle, to ensure its survival and transmission. This project uses microscopy techniques to assess the effects of mucus on parasite infectivity and genetic approaches to characterize factors involved at the parasite/IMB interface. It also uses a reverse genetic approach to identify genes that encode developmental stage-specific secreted effector proteins required for the very first stage of Toxoplasma infection.

Research Questions

How does Toxoplasma transition between metabolic distinct stages during infection?

Cellular differentiation is critical for Toxoplasma transmission and virulence. The parasite efficiently alternates between metabolically distinct forms. How Toxoplasma alternates between these disparate metabolic states during infection remains an open question. In this project, we focus on understanding the contribution of developmental regulated metabolic enzymes to Toxoplasma stage conversion.

How does Toxoplasma regulate gene expression during differentiation?

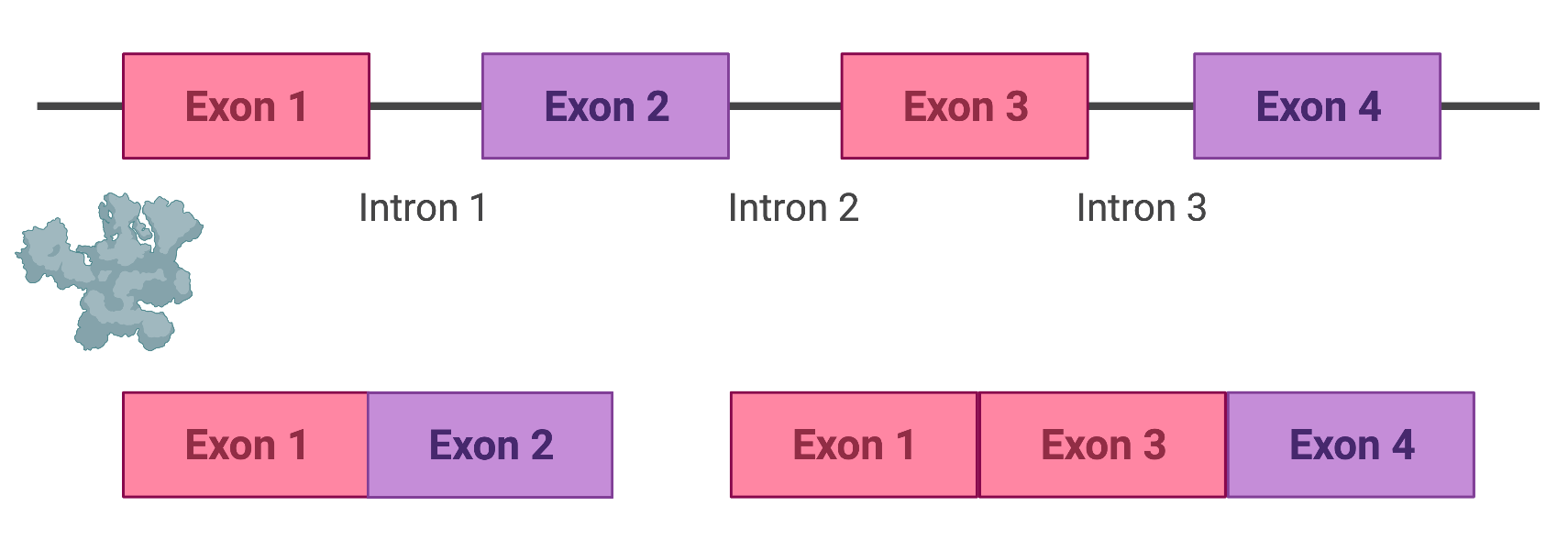

The transcriptomic and proteomic profiles of Toxoplasma are very dynamic. As the parasite progresses through the developmental cycle, it uses various molecular mechanisms to regulate gene expression. In this project, we assess the importance of alternative splicing in regulating gene expression during development.